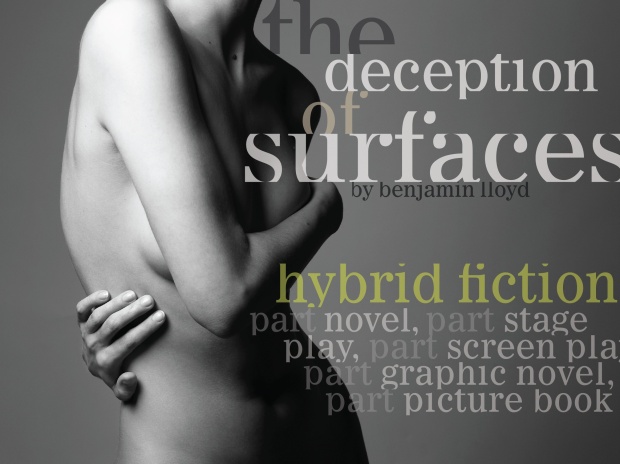

The Deception of Surfaces: Long-form excerpt

In 2008 I performed in LEAP, a long-form improvisation show at the Live Arts Fringe Festival in Philadelphia that year, directed by Bobbi Block. The experience had such a profound effect on me that, in the following year, as I worked on my book The Deception of Surfaces, I write a section of chapter which describes a long-form show. Now, I have co-founded my own long-form company, Bright Invention, so I thought it was time to share this, from chapter 9 of The Deception of Surfaces.

***

Act Two

The curtain opens and a middle aged woman stands center stage wearing loose fitting linen pants and plain green t-shirt. She has a full maternal body, short graying hair and magnetic eyes. Alice stares and sits up straighter. The woman clears her throat and an electric jolt shoots through Alice. When she speaks Alice is back in Neon, but now in the Taurus she’s muttering “Old fucking crazy lady . . . bag lady . . . stole my bag . . . Maddy!” She looks around the car at the other three, who are looking back at her with strange guilty smiles. “That’s Barbara Lewis,” says Henry quietly, “she teaches here . . . and she acts . . . out there.” And he points to the big windows above the stage, covered now by custom-cut curtains, holding back the street lights on Brown, twilight having come and gone.

Barbara is explaining Long-Form Improvisation: “ . . . collecting your cards right now. None of the actors, of course, have seen them in advance. All we have rehearsed are various forms which provide structure and give us things to try in the moment. It’s called ‘long-form’ to distinguish itself from ‘short-form improvisation’, which is usually just comic, you know, stuff you’ve seen on TV, Comedy Sportz, sketch comedy, stuff like that. So we will each pick two cards out of the basket, which will have a wish or a dream on it from one of you, and these cards will form the foundation of an hour-long improvisation we will offer you – may get funny, may get sad, who knows. And we will be accompanied by three musicians, Marcie on drums, Greg on bass and Daniel on guitar, who will also be improvising and responding to the actors’ work, or maybe initiating a kind of dynamic the actors have to fit into, except in one segment where it will be obvious they’re playing something they’ve learned. Um . . .” She looks to the musicians. “You guys ready? Okay. So we’ll begin in a minute.”

The cards from the Taurus have already been collected. “So . . . improvisation means . . . they’re making it up?” Alice asks.

“Si. No lines,” comes the growl from the back seat.

“No play!” chirps Uma.

“Have you done this?” Alice asks Henry.

“No way. Too scary,” he replies. The house lights fade to black.

A teenage girl with brown cork-screw hair, trendy Goth make-up and wearing what seems to Alice to be a cross between a coat and cape, comes on stage with a basket full of index cards. “Isabella,” whispers Henry. The trio plays something bouncy and unobtrusive. Then six actors – three men and three women of various ages and ethnicities, Barbara is one – walk in a line past Bella, pick two cards each out of the basket as they pass her and then stand in a line facing the audience. Bella exits, and the trio softens to just bass and brush sticks. The actors are reading the cards and some are smiling.

Each actor reads a card out loud in sequence. Everyone watching is having the exact same thought: will they read mine?

“I have always wanted to make love to two women.”

“Go to hell, you obnoxious pompous bastard!”

“Mom, you get drunk every night, it doesn’t matter that it’s only wine, you still get drunk.”

“I am addicted to daytime news on TV.”

“I really love unicorns and think maybe there’s really a live one somewhere.”

“I am in love with someone in this car.”

Then they read the second card they hold:

“I am paranoid no one takes me seriously.”

This actor pauses and collects himself: “I am dying.”

“Your dick is NOT so special!”

“I want the world to heal, and I believe I am a part of that healing.”

“Rachel, you really, really have to give him back his black t-shirt.” Somewhere in the darkness comes a squeal of recognition, and everyone laughs.

“I kind of hate my name.”

The actors begin to read the cards again, now overlapping, now building, using the energy of the language in the cards to inform how they are expressed, the trio building with them, until there is an astonishing crescendo of dreams, wishes, music and secrets, eventually only snippets understood, the music throbbing and all are joined. Like magic, it stops. Alice can hear breathing in the audience. The actors scatter to the wings.

mine’s up there, how did they, what are they

An African-American woman comes forward and sets a scene: “A high-school gym. There’s been a big party in it. Banners and streamers hang disheveled from the walls, the lights are dim, party . . . junk is strewn everywhere, moonlight comes in a high window, outside someone is playing rock music on a car radio.” She leaves and the band, somehow, makes rock music come from a car far away. A man and a woman- Barbara – enter the bare stage, now transformed into a gym in everyone’s imagination. They take each other in – lovers? Strangers? She extends a hand to him. He considers it and then shakes it formally – not what she is looking for. They invent a scene on the spot: he’s still married, she’s divorced, high school reunion, both feeling oddly drawn to each other, to the memory of the intense affair they once had. Towards the end, she says, I’m dying. Pee-U gasps. They hold each other, and then, surprisingly, they make out and he pulls her down to the floor.

A woman comes on stage and shouts drunkenly, “Your dick is not so special!” and the couple on the floor exit. A new man comes on stage, and they invent a comic scene outside a bar on South Street in which they are both drunk. During this scene, a third actor comes on and – as the main two freeze – explains to the audience that the man in question actually has a remarkably large penis. Then the fight continues, and resolves comically when he “whips it out” in front of a cop, who then goes home with him.

Then there is a scene in a car. This one is muddy and is trying to make something out of “I’m in love with someone in this car,” or “I’ve always wanted to make love with two women” but it needs more people in the car. It doesn’t really work with just the two women, who seem to be reaching for things to talk about, reaching to make it somehow about unresolved lesbian tension. The comic ending seems forced when the one in the driver’s seat looks out the window and says, “Is that . . . is that a unicorn?”

Alice laughs a little too loudly.

Another scene is set, in a hospital room. Two actors play very elderly people saying goodbye to a dear friend.

Uma remembers Andy’s book.

Barbara returns playing Megan from the high-school gym scene. An actor playing her teenage son asks her how the reunion was. This is a rich improvisation in which Barbara performs an amazingly subtle portrayal of someone simultaneously aroused and heartbroken by a memory.

this was the crazy bag lady?

Then, in a moment of genius, she begins to mime opening a bottle of wine, and the son just stares. The audience braces itself, and he says, “You know Mom, you get drunk every night.”

“It’s just wine.”

“It doesn’t matter.” The trio plays something heartbreaking in the transition.

Henry remembers carrying his Dad upstairs.

A scene begins with two men, one is miming looking through drawers. The other comes on. “Have you seen my black t-shirt?” the first one says, and the same squeal comes from the audience. This scene begins funny – two gay men accusing each other of being slobs, disorganized, not “on top of things” which gets a huge laugh. Then the trio begins to play something really sad, and the actors just stand there listening to it. The scene takes an unexpected turn as the second guy tell the first he’s been born again and wants to “cure his homosexuality”. “Pray with me,” he asks his lover. It ends with them praying together – one for a cure for homosexuality, the other for a cure for heartbreak.

Someone sits down on the platform outside the Taurus on Alice’s side, a suppliant specter in the darkness.

About a half-hour into the long-form, the trio strikes up some jaunty “lounge jazz” – the piece they’ve rehearsed. Three spots appear on the stage and three couples appear in the spots, each actor swirling imaginary drinks in their hands. It’s a party. Six brand new characters appear, more comic than any others seen yet. Over the course of five minutes, the three couples perform an improvised fugue, in which a new couple begins talking by taking a phrase or a word from the couple they interrupt. More astonishing, the three couples build comic stories which sustain and build through the interruptions, and three cards are woven thematically into the fugue: I’m addicted to daytime TV, I hate my name and I’m paranoid no one takes me seriously. At a cue from the band, the fugue builds and then ends with the three couples each using the word “Completely!” to end on a button. They exit and the audience erupts. Alice is aware of her dropped jaw.

The guy in the drunken sidewalk scene returns, stepping into a remaining spot center stage and speaking to us as that character (Barney, thick Philly accent). It begins comically, but then he begins to talk about his penis and everyone gets a little uncomfortable. It becomes clear that, instead of being a source of great pride for him, he actually feels freakish and embarrassed. “It’s like, the only thing I’m known for,” he says and Alice feels her face burning. “There’s a little more to me than that!” he says, snickering pathetically. We are left listening to someone who seems profoundly alone and sad. Pasqual pokes Alice on the shoulder, which kind of freaks her out.

Henry feels inadequate.

An actor sets a scene: a graveyard with a freshly dug grave, bright sunny day and flowers and chairs all around. Alice wonders, Megan? Or the old person in the hospital room? It turns out to be the latter. The trio plays something distant and spacey. The actress from the drunk scene and one of the actors from the black t-shirt scene play brother and sister. The sister’s deaf, and the actress performs using sign language. The brother avoids translating for her, and it’s hard to understand what the deal is between these two. Then another actress comes in, swings the deaf sister around to face her, and performs a kind of flashback in which she is the deceased lady, telling the deaf girl in exaggerated “talking-to-a-deaf-person” speech that she doesn’t want the boy to have any of her money, he’ll only spend it on drugs. The boy doesn’t hear any of this, and the new actress swings the girl back into the scene then exits. A moment passes and the boy signs and speaks: can we talk about the will? Translation becomes unnecessary as the scene becomes both a painful graveside conflict and an extraordinary physical performance by the “deaf sister.”

A man comes on and stands on stage doing something physically repetitive. It looks like he might be stamping something, or closing a series of boxes and then moving them around an office. A very bothered woman arrives and says “I’d like to change my name.” This turns out to be the funniest scene of the evening, in which the man tries to convince her that her name’s not so bad (it’s Utera Charleston McSnot). Then there is an escalation in which they debate the worthiness of various names and are periodically interrupted by a very old, eccentric and slightly deaf co-worker. Finally she leaves outraged, with her name intact.

Then there is a short scene which never really gels, about a guy who watches TV news all day. He yells at Barbara (playing his wife), “Go to hell, you pompous . . . bitch!”

A woman comes on stage and clearly begins working in a garden. Another woman, who becomes her daughter, resentfully helps her. In the midst of arguing about whether or not gardening is a waste of time, the first woman stands and comes down stage. A spot light fades up on her. She tells a simple story about being a devout Quaker, about how of all the Testimonies the one that has always mattered to her most is Stewardship. There’s so little she can do, she says, in the face of all the heartbreak and wreckage in the world, at least she can care for one little patch of it. “You see,” she says, “I want the world to heal, and I want to be a part of that healing.” She returns to the garden and the woman playing her daughter heaps abuse on her before leaving.

Uma wants to strangle the daughter.

The same African American woman who set the first scene (and played a variety of roles including Utera), comes back on stage. “Years later, we’re back in the high school gym. There’s been a reunion, but this time, there’s no music.” She stays on stage now, and wanders around the empty space. The quiet in the Assembly Room has substance to it, it’s a Faberge quiet: ornate, hard and fragile. The actor who played Megan’s teenage son comes on, slow and quiet. Somehow, by the way he walks, we know he’s a grown man now. They see each other. At the same time, they run into each other’s arms and kiss furiously. A story is told between them, and between everyone present, about a mother’s death, about an imperfect family, about interracial love, about the doubts of growing older, about the passionate need for connection. It’s a story nobody and everybody in the Assembly Room has written together, and it is infused by the confessions, dreams and secret wishes of the witnesses, who have come here to be close, in a world which continually forces them apart.

The man and woman end on the floor of the gym, he on the floor holding her in his lap, both in a pool of moonlight Bella has conjured from her lightboard on the balcony. In their embrace all are embraced. Their story, unique to that fleeting evening in May 2020, never to be seen or heard again, is at the same time everyone’s story, older than the city and waiting to be told again. And when she asks if they can see each other again soon, the ache the witnesses feel as he pauses, stands and walks thoughtfully downstage, is close to unbearable. And when he turns and says, “Yes. Yes I think we can. Yes . . . I’d really like that,” tectonic plates of feeling shift in the great room the Shelly brothers built, something of great consequence is released and bathes everyone in grateful affirmation. It is a great exhalation: yes. It is a prayer: yes, I think we can. It is a tearful murmur: yes, I’d like that.

Uma thinks of her brand new life.

Pasqual regrets not saying it when he had the chance.

Henry floats in the affirmation. And so does Alice.

The six actors stand now in a line holding hands and the audiences stands and yells, applauding. The actors bow and bow and bow. The house lights rise a little and the trio stays, playing some old Django Reinhardt tune. The whole thing has taken about half an hour. Alice leans back, takes a deep breath, wipes her face and says to Henry “They made all that up?”